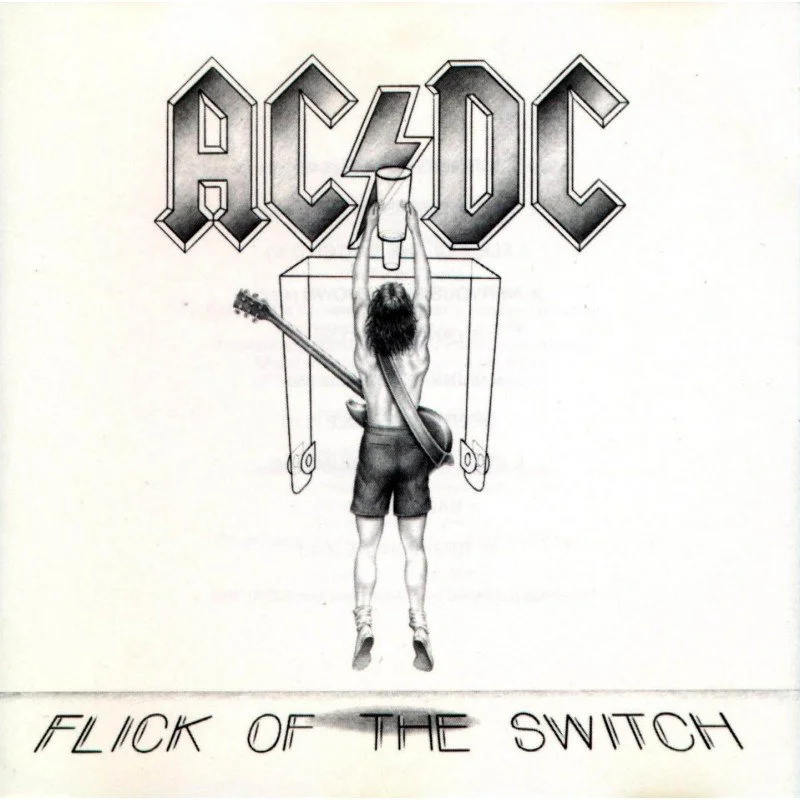

AC/DC’s ‘Flick of the Switch’: The Sound of the Lights Going Out

There’s a peculiar kind of hangover that sets in after you’ve been living like gods—as AC/DC, thundering into the dawn of the 80s. It didn’t happen right away — not after Highway to Hell, not even after Back in Black. But by 1983, the party lights were flickering. The air smelled like stale beer and burnt circuits. Malcolm and Angus Young, eternal schoolboys in short pants and bad intentions, decided they’d had enough of Mutt Lange’s meticulous, metronomic tyranny. They wanted it raw again — back to barroom thunder and the stench of blood, sweat, and twelve-dollar bourbon. So they threw Mutt overboard, set up the mics in Nassau, and produced themselves.

The result was 1983’s Flick of the Switch — the sound of AC/DC yanking down the main lever after a decade of thunder — only to find the whole damn circuit blown and the room going dark.

There’s a certain noble self-sabotage at work here. “Let’s get back to basics,” they said, as if basics were some kind of magic key. But basics without inspiration is just barbed wire around an empty lot. Engineer Tony Platt recalled that Malcolm rejected his first mixes because they sounded too much like Back in Black. That’s like turning down a Ferrari because it drives too well. What they kept instead was an album that sounds like it was recorded in a submarine filled with cigarette smoke and self-doubt.

Listen to “Rising Power,” that limp opener that stumbles out of the gate like a hungover prizefighter. The riffs are there, but the voltage isn’t. Compare it to the sleek menace of “For Those About to Rock” and you hear the current drop by half. Flick isn’t without its moments — “Guns for Hire” and the title track have genuine bite — but they feel like fragments of better songs that never showed up to rehearsal.

Without Lange’s forensic ear, AC/DC were finally exposed. Lange had been their mad scientist, layering rhythm guitars with the precision of an airstrike, sculpting every snare crack into an act of war. Strip that away, and suddenly you could hear the rust — the repetition, the blunt-force bravado. “My body’s full of juice,” Brian Johnson bellows on “Rising Power,” and you can practically see Bon Scott smirking from the afterlife. Bon’s innuendo dripped with sleaze and wit; Brian’s just sounds like a weightlifting injury.

Still, Flick deserves a kind of respect for what it isn’t. It isn’t polished, or pandering, or chasing radio trends. It’s five blokes, one downed drummer, and a bottle of bad rum trying to remember what it felt like to be dangerous. The tragedy is that it shows just how far they’d drifted from that feeling.

Phil Rudd’s departure hangs over this record like a ghost in a barroom mirror. He was AC/DC’s metronome, the unflappable heartbeat beneath all the chaos. By ’83, that heartbeat was irregular. Booze, drugs, and a fractured love life did what no rival band ever could: they knocked him out cold. His firing was swift and merciless — Malcolm’s dictatorship in full swing. “Hard hitting rock drummer wanted,” read the ad that would eventually bring Simon Wright into the fold. It might as well have said “Apply if you can survive us.”

When the record hit stores, Atlantic Records shrugged. No singles, no fanfare. Flick debuted, flopped, and faded. The tour sputtered. Whole arenas half-filled. The mighty AC/DC, reduced to playing to the echo of their own amplifiers.

Critics lined up with sharpened quills. Creem called it “plodding,” NME compared it unfavorably to Pyromania, and by the time the dust settled, even diehards were scratching their heads. Flick’s commercial fall from grace wasn’t instant death — it still went platinum in the US — but it marked the end of AC/DC’s imperial phase. The empire was cracking, and they’d need The Razor’s Edge seven years later to truly rebuild it.

Still, there’s something perversely endearing about Flick of the Switch. It’s AC/DC’s Let It Be if everyone had been drunk, angry, and locked in a warehouse with too many amps and not enough ideas. It’s their anti-anthem album — a record made by a band too proud to chase pop-metal trends, too stubborn to ask for help, too drunk to notice the lights had already gone out.

Revisit Flick now, four decades later, and it plays like a cautionary tale about creative control. For every band that’s ever said, “We’ll produce it ourselves,” this is the sound of the trapdoor opening. Yet there’s a human warmth in that failure — the kind of bruised authenticity that Mutt Lange’s shiny perfectionism could never capture. Beneath the flat snare and muffled mix, you can still feel Angus’s knuckles bleeding, Malcolm’s jaw clenching, and Brian shouting into the void like he’s trying to resurrect Bon.

For a band that made a career out of electricity, Flick of the Switch was the moment they forgot to pay the bill. But the lights never go out forever in AC/DC’s world. They just dim long enough to make the next spark feel like salvation.