Cowboy Bezos and the Giggling Hyena: Notes from the Enlightenment’s Last Freak Show

Some Kind of Monster is a two-hour slow-motion car crash, a documentary that peels back Metallica’s stadium-sized façade to reveal a fractured band in midlife crisis therapy, spilling its guts on camera like a bloated fish on a dock. It’s a parade of jaw-dropping absurdity: James Hetfield storming off to rehab in a cloud of bile, Kirk Hammett trying to hold the band together like a yoga instructor refereeing a knife fight, and a therapist billing more per hour than a Colombian coke dealer. Yet in this cavalcade of unintentional comedy, there’s one scene that soars above the rest: Lars Ulrich, tucked in a back room at an art auction, giggling like a lunatic while his private art collection sells for millions.

He’s not laughing at a joke. He’s laughing at the absurdity—kicking his feet up while paintings he bought on a whim are suddenly worth more than most fans will earn in their entire lives. He giggles like a man watching the floor tilt under his feet, like he’s the only one who knows the cosmic joke: art has been stripped, gutted, and converted into stock certificates, and somehow he’s the lucky bastard cashing the checks. In a film full of surreal self-parody, Lars’s laughter is the purest crackle of truth: the game is insane, and the only sane reaction left is to laugh until your ribs break.

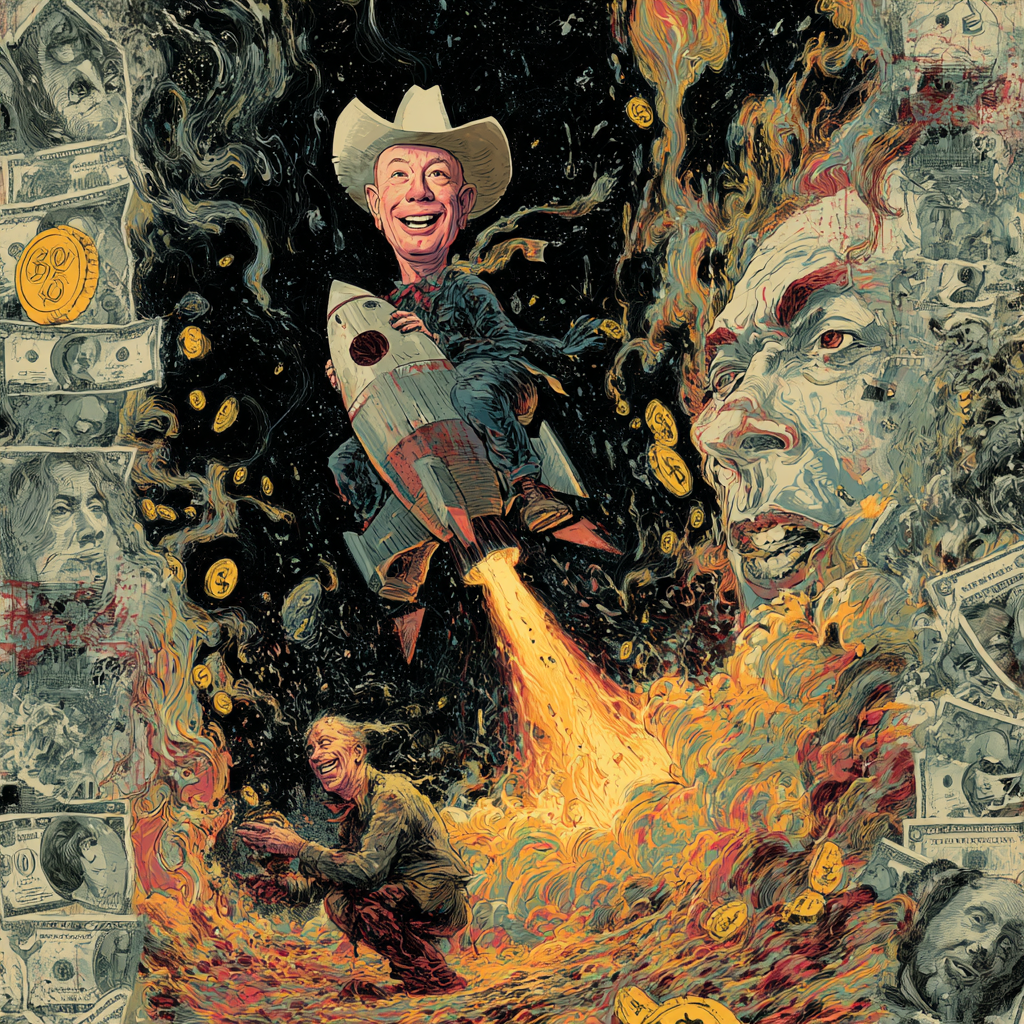

Now spin the camera across two decades and a few hundred billion dollars to Jeff Bezos, standing on a launchpad in 2021, dumbly grinning in his cowboy hat as he prepares to shoot himself into the stratosphere on a Blue Origin joyride. Before liftoff, a petition was circulating to bar him from returning to Earth, signed by more than 200,000 people who would happily strap him to a rocket and fire him at Mars permanently. Why? Because Bezos had been busy sermonizing about humanity’s “destiny” to leave Earth behind.

In a 2018 interview, he laid it out with the icy calm of a man who thinks God is a spreadsheet: civilization’s “metabolic rate” is growing too fast, we’ll need more energy than Earth can provide, so the only solution is to colonize space. His vision? A trillion humans scattered through the solar system, pumping out a thousand Einsteins and a thousand Mozarts, because apparently genius can be farmed like soybeans if you just scale up the population. He said this with a straight face, as if it was self-evident, as if mathematics had revealed a cosmic mandate.

Lars giggles at the absurdity. Bezos does not giggle. He believes.

And that’s the split-screen tragedy of modern civilization. On one side, the drummer of the world’s biggest metal band, reduced to a goblin giggle in the back room of an auction house, giddily spilling champagne while watching sacred art dissolve into market fodder. On the other, the richest man in human history, a true believer in the cult of Reason, selling us on a cosmic pyramid scheme where progress is measured in population density and Mozart clones per capita.

The French revolutionaries tried this in the late-eighteenth century: dethroning priests, enthroning Reason, and baptizing their citizens in the gleaming, “humane” cut of the guillotine. Paul Kingsnorth, in his essay “Critique of Pure Reason” (from his book Against the Machine), reminds us that this was the Enlightenment’s great experiment—Reason elevated to the status of deity, temples of Rational Man erected where churches once stood, philosophy replacing faith. It promised freedom, progress, and virtue. What it delivered was blood in the streets, priests hunted like vermin, and Robespierre grinning at his own execution device before it took his head. The guillotine wasn’t a barbaric regression; it was the logical endpoint of Reason-as-God. Rational death, mass-produced and marketed as humane progress.

Bezos’s rocket is that guillotine turned skyward: a stainless-steel sermon to the cult of Reason, promising salvation by expansion, infinity by colonization. The logic is the same—more growth, more people, more genius, more “progress.” It’s the same Enlightenment utopianism Kingsnorth skewers: the belief that human destiny is a math equation, that chaos and myth can be tamed with enough wattage, that the sacred can be converted into numbers without consequence. Bezos doesn’t laugh because he doesn’t see the joke; he’s the high priest now, preaching growth as gospel, selling starlight futures while the earth beneath us coughs up fire.

And this is why Lars’s hyena-giggle in Some Kind of Monster lands harder than Bezos’s billion-dollar sermons. In a film stuffed with therapy-speak and rock-star neuroses, his cracked laughter was the only sane noise in the room: the bark of a man who recognized that the carnival had collapsed into lunacy. Bezos, on the other hand, has swallowed the Enlightenment’s poison whole and calls it destiny. Lars laughs at the madness; Bezos tries to weaponize it. One is a drummer cashing in on the absurd; the other is a plutocrat selling us on a cosmic meat-grinder where a trillion souls churn out genius like widgets on a factory line.

That’s the punchline, and it’s not funny: the Metallica drummer cackling at his Sotheby’s catalogue is closer to truth than the richest man alive with a rocket full of Reason. Lars lets the absurdity spill out of his lungs. Bezos builds temples to it and straps us all in for the ride. And if history teaches us anything—from Paris in 1793 to the launchpad in 2021—it’s that when Reason is crowned king, the guillotine is never far behind. Only this time it’s pointed at the stars, and Bezos is laughing last.